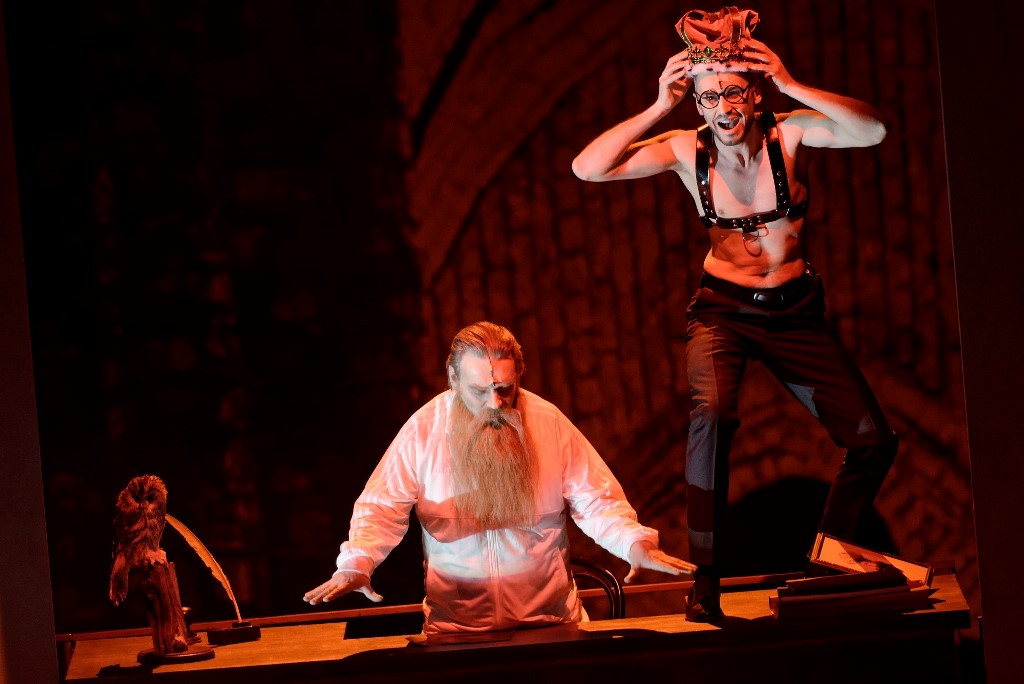

To mark the 100th anniversary of the Republic of Lithuania, the Opera and Ballet Theatre commissioned the opera from composer Gintaras Sodeika (director Oskaras Koršunovas, librettist Sigitas Parulskis). The three artists first met in 1997, when they were staging the performance P.S. File O.K. (Lith. P. S. Byla O. K.), and later cooperated in the performance Hello Sonya New Year (Lith. Labas Sonia Nauji metai) based on the play Christmas at the Ivanov's by Alexander Vvedensky (Parulskis translated the texts). This time, they attempted to once again apply absurd key to the state birthday celebration by attributing elements of dada genre and farce to opera.

Paulina Nalivaikaitė (Kultūros barai) writes, “By appealing to the present of the genre, the authors have chosen a playful form of 'opera within opera.' To cheer bored God up Satan offers a game, the aim of which is to show the past of Lithuania (that God does not even remember about) as a kind of opera. Yet certain solutions struck me as rather straightforward. In the first scene, God is riding a stationary bike and image projections (author Rimas Sakalauskas) are showing space, flying asteroid fragments, and spaceships, as if we were travelling in a time machine; then, all of a sudden, bottles of Coca-Cola and Vytautas appear. /.../ Anyway, all this seems to be kitsch, just like the second scene that depicts the times of Vytautas the Great, where, without warning, latex-clad prostitutes (Satan's escort) emerge without adding any purposeful meaning to the performance except leaving the impression of a cheap trick and chaos. The chaos is further intensified by strange chronological leaps among scenes - after the first, introductory scene, where Satan offers showing the history of Lithuania as an opera to God, we are taken to the times of Vytautas, and then, immediately, to the eve of 1918.

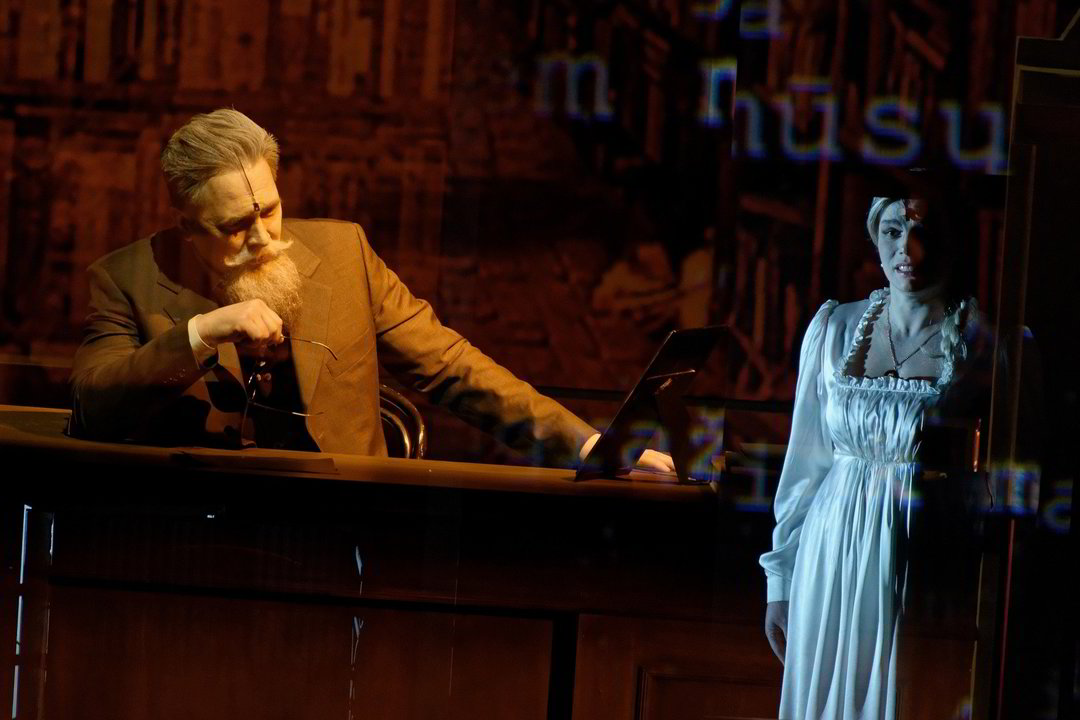

Highly professional quality video projections by Rimas Sakalauskas have left a great impression and revealed the possibilities of contemporary opera. 3D effects, meticulous graphical presentation, attention to details, and well-directed photographs sometimes serve as aesthetic, sometimes as provocative (for example, the faces of Lithuanian politicians or erotic photos of the early 20th century women), and yet always effective counterbalance to most of what is happening on the stage.”

Musicologist Beata Baublinskienė (rytas.lt) admits having noticed that, “directors who choose radical and often shocking means of expression on the dramatic stage tend to be more moderate in opera, showing no intention whatsoever to demolish the 'sanctuary' of genre traditions (remember Elixir of Love (Lith. Meilės eliksyras) or Fidelio (Lith. Fidelijus) by the same director). The set design is modern, and, by the way, singers are great actors. However, here you won't experience the bare nerves that are normally associated with the works by Oskaras Koršunovas.”

Theatre critic Vaidas Jauniškis is even more ruthless, “Post Futurum has proved that these creators are a hundred years away from contemporary opera and can only understand statehood from an ironic perspective. Unfortunately, instead of serving as a conceptual solution, this open late 19th century amateur performance style has turned out to be a glaring attempt to find some way out by saying something and yet practically nothing.” (15min.lt)

According to opera critic Rima Jūraitė (Menų faktūra), “Post Futurum undoubtedly claims to be the genre of postopera (in terms of contemporary musical language and libretto specifics), and yet it is not par excellence. This happens when trying to parody opera clichés creators fail to distance themselves from traditional genre attributes that deny opera relativity. /.../ National topics are intimidating because of their pathos and risk of becoming merely one more costume staging, whereas sublimated heroics are breathing heavily into the faces of spectators with their stern graveness. When one considers these aspects, the creators of Post Futurum have escaped the trap of national opera format.”