Marija Baranauskaitė is one of the first artists of Lithuanian contemporary circus, who studied performing as well as contemporary dance at Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre. Having acquired her diploma, the artist went to International School of Theatre LASSAAD in Brussels, where she spent a year, and then - to France. After the admission to Philippe Gaulier School of Theatre, Marija Baranauskaitė decided that clownery and contemporary circus had to form the basis of her creation. In France, she also got the ideas for her first and one of the first clownery performances in Lithuania The Sofa Project (Lith. Sofos projektas).

Marija claims that the target audience of The Sofa Project aren't people but rather sofas. With this position in mind, the creator presented her work for the people and sofas of Lithuania, Latvia, Great Britain, France, and Germany. In the performance, Marija employes ingeniously the elements of dance, clownery, performance, music and video to pose an unexpected question: how are we, people, related to sofas? What can we learn about ourselves and the others from these relations? What passions do sofas have?

Marija was inspired to dedicate her performance not to people by contemporary circus artists creating for cats, dogs, and plants. “I started considering - if contemporary art has progressed far enough as not to seek to be understood, then, perhaps, we don't need a conscious spectator? Maybe a creative act is possible without any audience at all?” Marija wondered. “To me, the essence of circus is to do something impossible. This doesn't have to be the crossing of physical bodily boundaries. I cross boundaries conceptually.”

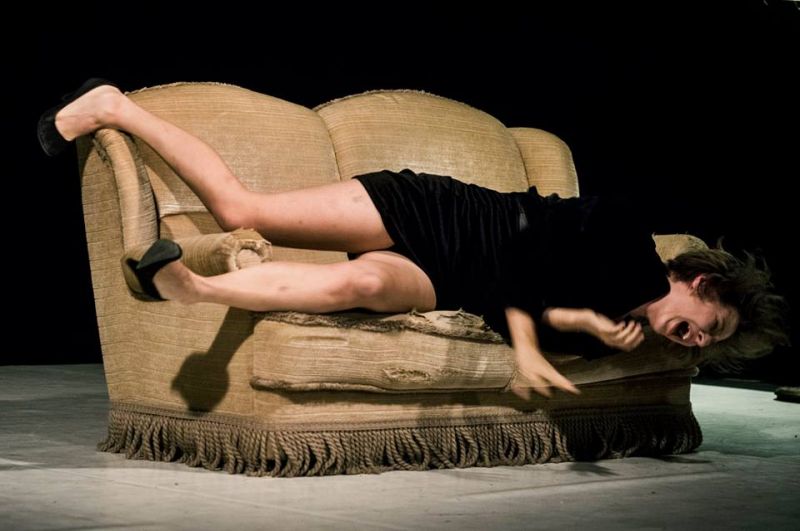

“She is seated on a small beige settee, wearing a black dress and high-heeled shoes. Her dishevelled hair gives a warning that she's unpredictable,” critic Ieva Tumanovičiūtė (7 meno dienos) presents the performance. Marija Baranauskaitė referred to the first performances of The Sofa Project as “work in progress” and critic Dovilė Zavedskaitė (menufaktura.lt) claims that, “it's difficult to imagine this project as finished: the status of never complete suits the performance.” According to the critic, “A sofa as an object could, perhaps, be really boring if the performer plunged into stereotypical contemplations on the life of sofas. Which, actually she does, but only insofar as the audience sticks to human qualities. Having defined new rules - to become similar to a sofa; not to laugh, not to watch, not to move and not to feel as humans do - Marija steps up the fight against herself in the face of sofas, and constanly conjures sensible, animate, and slightly sensitive tricks.”

Marija is the only live performer in the performance. She regards sofas as her audience; however, it's obvious that a part of them - just like a human audience - constitutes a part of the created action. At the beginning of the performance, Marija imposes some conditions on spectators - to hide, to cover themselves with clothes or blankets so as to become invisible, to turn into sofas or just to leave the hall and to familiarize with The Sofa Project outside the hall, through video imaging. This sometimes creates curious situations, in which the creator-clown emerges, “Marija's stage life is fascinating in that she is sort of afraid of her own boldness: having unhesitatingly asked the head of the festival to leave the hall just because the latter refused to live the life of a sofa, Marija immediately feels out of breath. Such fright accompanying the courage to behave according to her own rules actually determines the trust of the audience in Marija's openness and non-fear to be vulnerable,” critic Dovilė Zavedskaitė writes and continues, “Marija simultaneously enjoys her autocracy, absolute obedience of the sofas surrounding her, and marvels that man - non-sofa - has accepted her rules and plays according to them without any resistence. /.../ by asking not pay any attention to her, Marija actually screams for attention: one moment she adorns her head and dances a shaman dance, the next - she upturns the sofa, climbs on it and starts singing a song in an unctrolleable voice; one moment she shows how to treat a sofa and teaches the others, the next - she keeps checking how the people hiding under a cloth and gathering dust with their covered mouths/eyes/noses are doing.”

Ieva Tumanovičiūtė describes the ending of the performance as, “the meditation of a sofa” that joins pieces of furniture and people into one big circle and “encourages the latter to relax and not to take themselves too seriously.” Sofas are silent, whereas people start thinking aloud: who told that people cannot be sofas? A sofa is a sofa only when man defines it like that. If a human being didn't see it or didn't think about it, would it still be a sofa?